Secrets for a long life

A framework for building businesses and ecosystems that deliver sustainable long term value

This post was going to be about friction. I struggled with that one for a couple of weeks but it was just making me angry. And I had nothing to say (beyond grin and bear it!) So I have put it on the shelf and written about ideas that make me think and offer hope instead.

Taking the Baltic air

About 30 years ago I attended a course on business strategy in Denmark. The venue was a seaside hotel somewhere south of Copenhagen. I loved walking the shoreline every morning. Feeling the cool Baltic air and watching the year round open water swimmers.

The course itself was strange. The hotel was nice enough but we were served thick slabs of rare roast beef for lunch and dinner every day. Unusual even then. I was not clear why I had been chosen to attend. I struggled with the content. I guess I lacked the experience or intellect to understand the grand ideas. I don’t remember specifics but my general impression is I found the whole thing unsettling.

Mintzberg and De Geus

Yet I was introduced to two thinkers who had a profound influence on me - maybe some ideas stuck after all.

The first of these is Henry Mintzberg. We were shown a hilarious video where he explains the famous Honda B case study. I am not sure this version is the original but still funny to watch.

Most management theories are the result of 20/20 hindsight imposing structure on complex and messy reality. Mintzberg’s description of Honda’s conquest of the US motorcycle market in the 1960’s is a memorable example of the opposite.

I think of this often when I see top down plans built in the straitjacket of “best practice” business theory. It reminds me of a famous saying by another well know business thinker “Culture eats strategy for breakfast.”

Which leads me to the main subject of this post, Arie De Geus. In a video I cannot now find, he talked about his early career. De Geus was the strategic planning manager of Royal Dutch Shell during the oil price shocks of the 1970s. When the crisis hit, he was able to pull a scenario plan off the shelf that set out a response for oil prices doubling overnight.

The whole idea of big oil may be unattractive these days but the depth of thinking amazed me. In some ways his example of strategic planning appears the opposite of Mintzberg. After all, Mintzberg wrote an academic book called The Rise and Fall of Strategic Planning.

At the time and since, I took a different view. The focus of both men was considering options and possibilities. They were both driven by context and reality not theory. And they advocate making choices by thinking forward not backward.

The Living Company

I have been fascinated by these ideas ever since. More often than not that leads me back to a short book by Arie De Geus, the Living Company.

Its by far my favourite business book of all time. Offhand, I can’t think of another one that I have read more than once. Most are so bad I give up halfway through.

De Geus looks at large companies as independent living organisms. Its a great analogy to capture the unique context and evolving nature of each business situation. His question is why do most companies have a shorter lifespan than a human being. And what distinguishes those that live for much longer.

He has a simple framework for long lived business. What we might now call sustainable:

Every great company is a learning company. Learning throughout its history and acting in response to the lessons learned. Perhaps by favourite thought - Decision making is a learning activity.

Persona. Only people learn. Companies acquire a personality but that is an artefact of the people and culture that built the company and take it forward.

Profit v longevity is a false choice.

Tolerance. Great companies tolerate a variety of approaches, strategies and people. They allow different parts of the company to adapt, even to compete with each other. They allow diversity and maintain a delicate balance between freedom and control. This involves some waste but it provides greater resilience. Building what Taleb calls antifragile systems - many of his ideas are foreshadowed in this chapter.

Evolution. Key to managing the variety is evolution not revolution. Conservative approaches to financing retain reserves for resilience. Diversification of power and systems of resistance to power are also essential.

I love the simplicity and flexibility. Its a sustainable way of thinking, not a formula for get rich quick success. Its about building great businesses not achieving high returns.

Why don’t we aim to build companies this way rather than designing for VC returns?

Why don’t we build ecosystems this way?

And one final question. Many of his examples are rooted in cultures I admire - Scandinavia, Finland, Japan. Perhaps we also need to pay attention to building a better society, a sustainable economy and a different business culture?

Observations

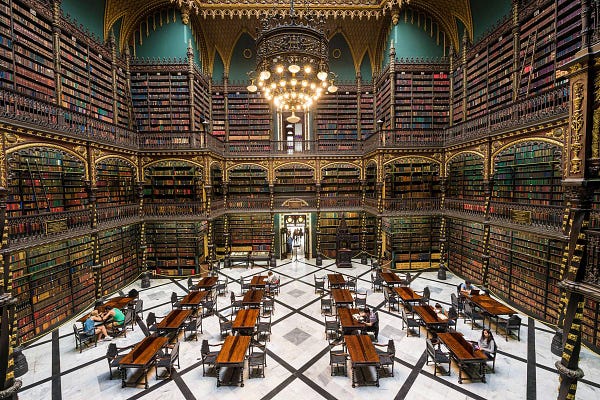

The world’s most beautiful libraries. Just because.

Elinor Ostrom

I have been a fan of Elinor Ostrom for a long time. This book review by Martin Sústrik provides a neat introduction to her work. Her theme was finding the best ways to manage shared, scarce resources (often called common pool resources). She believed the "tragedy of the commons" was an avoidable fallacy not an economic insight. She also demonstrates that neither state central nationalisation or competitive privatisation offer real solutions.

There are deep lessons here for the shared commons of knowledge which underpins so much of the global tech ecosystem. Her ideas also resonate in thinking about collective solutions to the COVID crisis and the recovery which will follow. Yet the concepts are not often part of the debate. Ideological ideas from the left or right such as nationalism and UBI are analysed to death. Real solutions based on bottom up local communities not top down Government answers have never been more needed.

By the way, if all this sounds radical Ms Ostrom was also the first woman to win the Nobel award for Economics.

David Graeber

David Graeber died a couple of weeks ago. He was a clear thinker and a distinctive voice. His famous essay quoted above is a great but uncomfortable read. I fear I may have spent a lot of my life doing bullshit jobs….

“..what would happen were this entire class of people to simply disappear? Say what you like about nurses, garbage collectors, or mechanics, it's obvious that were they to vanish in a puff of smoke, the results would be immediate and catastrophic….it is the only explanation for why, despite our technological capacities, we are not all working 3–4 hour days.”

David Graeber - On the Phenomenon of Bullshit Jobs: A Work Rant. By the way he wrote an entire book on the subject.

Who cares about Unicorns?

Who cares about Unicorns? French entrepreneurs nail the right question. Business is about great products, value for customers and jobs. Measuring success by bullshit valuations sets the wrong incentives. Maybe we can build better ecosystems and have more impact if we listen to entrepreneurs a bit more?

Kenny--really enjoy your work. Learn a lot. Thank you for the time putting these together.